|

By Lindsey Sawin When Gene Lowrey became a part of the cattle feeding industry 30 years ago, he hit the ground running, with a desire to learn, a passion to give back and to advocate for the rest of the industry, which is likely the reason he is serving as the Texas Cattle Feeders Association Chairman. “I was going to will my way through no matter what,” Lowrey said. “I was going to work hard, be honest, listen to people who knew more than I did and I was going to learn everything I could.” Lowrey grew up on a commercial cow-calf operation in Southwest Alabama. Growing up on the ranch taught him the value of hard work, the importance of dedication and created a love for the cattle industry. He packed his bags in 1991 and moved to Stillwater, Oklahoma to pursue an animal science and business degree at Oklahoma State University (OSU). He left with a burning passion to be involved in the cattle business. “Leaving home wasn’t the easiest thing, but on the other side of that I found a great opportunity where I am, and I have been involved with things that I had no idea I would ever be involved,” he said. While in college, he worked at the OSU Wheat Pasture Research Station. It was there that he was introduced to cattle feeding. Some of the cattle on trial were sent to Cimarron Feeders to be finished. Lowrey met John Rakestraw at the feedyard and later Rakestraw offered him his first job after college. He started as a feedlot trainee and has not looked back since. “I had no idea that I would stay this long, but I have no regrets, nor would I do anything different. I have learned so much and met so many great people,” he said. “If I would have picked up and moved back home and lived in my own little world, never ever would I have been exposed to the things I have been exposed.” A desire to learn

Growing up in an area of the country that is not conducive to feeding cattle meant that Lowrey had not been around the size or scale of operation that was Cimarron Feeders. “The learning curve was pretty steep, I knew nothing about nothing,” he said with a laugh. “I had never been exposed to anything of that scale. The most cattle I had ever seen was at a sale barn coming from the southeast.” While the knowledge gap was big, Lowrey was passionate about gaining the knowledge it took to manage a feedyard and to manage people. Lowrey spent four years at Cimarron Feeders where he said he learned everything he could before moving to Hartley Feeders in 1998. He started there as the feed manager and again took every opportunity to learn. Eventually, he was promoted to general manager at Hartley Feeders and in 2009 he moved to XIT Feeders in Dalhart where he currently works. He loves being able to share his knowledge with young employees and help them grow. “A big part our company’s philosophy is developing people from within,” Lowrey said. “It is tremendously exciting for me to see young people move up through the organization and take on more responsibility and produce great results. That is the thing that keeps me going at the feedyard.” Paying it forward Giving back to the industry that has provided him with unique opportunities is something Lowrey set out to do since the beginning. “I always felt that if I was going to make my living in this industry, I needed to give back,” Lowrey said. TCFA has provided him the opportunity to give back and play a role in moving the industry forward. Lowrey is the kind of leader that is quick to listen, while bringing knowledge and perspective to the table, TCFA President and CEO Ben Weinheimer said. “Gene Lowrey has been an engaged and productive member of TCFA for many years,” Weinheimer said. “He is passionate about feeding cattle and upholding the values of the industry and association while moving them both forward. We are thankful for his leadership and willingness to represent TCFA membership this year.” Part of Lowrey’s efforts to give back include leaving the feedyard to make trips to Austin and Washington D.C. “While I may not be at the feedyard, I am still trying to help the people who are at the feedyard by making sure that the things that don’t need to happen don’t happen and that the things that need to happen do happen,” Lowrey explained. “I think it is a privilege to be a part of all of that.” In his many years of involvement within the feedyard industry, he has seen it evolve and grow. As chairman, he wants to see the industry continue to make progress. “If we get complacent, the world is going to pass us by and it will replace us with something that doesn’t have the story and doesn’t have the benefits that our product has,” Lowrey said. He is ready to take on the challenges thrown the industry’s way this year. He wants members to pull up a seat at the table and continue to move forward together. “Everybody has a chance to say what they need to say and be a part of making the decisions and getting the decisions down to the people who need to hear them,” Lowrey said. He wants to leave the industry better than where it was when he started. “It is a privilege to do this, and I do not take it lightly. I will do whatever the association and industry needs,” said Lowrey. “I care deeply for it, and it has afforded me a very good living. I have raised my family, and I am going to keep doing what I can to make it better.” A passion for the cattle business was instilled in Lowrey years ago on a small family cattle operation, a passion that has not been lost in the shuffle of life but has grown and developed into the thing that drives him. “The industry has to remember that we are there for a bigger purpose,” said Lowrey. “It gets me up and going to work each day. Being a part of feeding people is something that feels good. It gives everyone a sense of higher purpose. We are able to do what we do, and people enjoy a good steak or hamburger. It is more than the long hours and cold days and hot days. We are doing something people like and want to eat.”

0 Comments

The Amarillo area beef community presented a check for $100,500 to the Snack Pak 4 Kids (SP4K) Beef Fund. One hundred percent of the money raised will provide food-insecure students with high-quality beef protein through the Snack Pak 4 Kids weekend backpack program. The check was presented at the fifth annual Beef 4 Kids golf tournament.

"In the past five years, more than $500,000 has been raised through the B4K golf tournament, to ensure kids in 50 area communities have access to protein every weekend. It is a blessing that our agriculture partners have come together to make this possible," said Dyron Howell, Founder and Executive Director of Snack Pak 4 Kids. The SP4K Beef Fund launched in October 2017. The program was designed to provide more protein over the weekend for hungry students in the Texas Panhandle. This year’s tournament pushed the fund to over half a million dollars in donations to the Beef Fund in just five years. Each year, local teachers answer survey questions from SP4K to ensure the program is adequately serving students in the area. “The students who get the bags are better mentally, physically and spiritually for having food over the weekends. They are alert, thinking and participating all the time during class and lab,” said a local teacher. Protein is an important addition to every Snack Pak bag and beef provides ten essential nutrients and vitamins, including protein, zinc and iron – three key nutrients that are essential for proper growth and development of children. “Texas Cattle Feeders Association is thankful for the strong partnership with Snack Pak 4 Kids and the opportunity to work with the community to provide high-quality beef protein to students in the area,” said Lindsey Sawin, TCFA Communications Coordinator. “Cattle feeders are dedicated stewards of their communities, and we are honored to be able to give back at the Beef 4 Kids Golf Tournament.” TCFA would like to thank the sponsors and golfers who made this year’s event possible. Major sponsoring organizations include Amarillo National Bank, Baptist Community Services, Bezner Beef, Cactus Cares, Cargill, Caviness, Champion Feeders, CoBank, Elanco, Five Rivers, Friona Industries, Jax Transport, Kemin, Kirkland Feedyard, Microtechnologies/MWI, Tyson, Underwood Law Firm and Upshaw Insurance.

By Hattie Robb

From farming to feeding cattle, production agriculture has always been in the cards for Michael Bezner.

“I enjoy growing things and the lifestyle that encompasses agriculture. I think it’s just in my DNA,” he says with a laugh. Growing up on his family’s farm and stocker operation in Dalhart, Bezner worked alongside his grandfather A.J. “Doc”, his dad, Jody, and his two brothers, Mitchel and Stephen, before heading to college. Bezner attended Texas A&M University where he studied animal science and was a member of both the meat and livestock judging teams. After graduating, Bezner worked under Bob Price in the livestock analyst office at the former Cargill Investor Services in Chicago. But the windy city blew him back to the family business in 1991, and Bezner has been preserving that same lifestyle ever since. Proving there’s no place like home, he and his wife, Camille, currently reside in Dalhart and have three daughters, along with one granddaughter. “I always knew I’d end up back here. Sure, we have good days and bad days, but there’s nowhere else I’d rather be.” From the Ground Up With farming in his blood and a desire to keep producing, Bezner decided to expand the family business in 1997 by building what is now a 20,000-head capacity feedyard in Texline, known as Bezner Beef. “I saw several synergies like manure availability, crop marketing and residue utilization between farming and feeding cattle that have proven to be beneficial for both sides of our business,” he says. Building a feedyard from scratch was no easy feat, and Bezner was determined to do it right the first time. Before breaking ground, he toured several operations in cattle feeding country and sought guidance from experienced industry mentors ranging from feedyard owners, managers, nutritionists, veterinarians, engineers and more. He researched everything from dirt work to mill operations to cattle handling so he could ensure cattle at Bezner Beef would be cared for in the best environment possible. The next step was to fill pens. According to Bezner, developing relationships was crucial in obtaining and keeping customers. He managed to do just that and shipped Bezner Beef’s first round of finished cattle in 1998. “It was a process, but people gave us a try,” Bezner says. “We had a tremendous head start because my dad and grandad have been here for more than 30 years. I was just lucky to have family before me that had a really good reputation in terms of honesty and integrity, and our customers trusted in us.” That reputation of trust remains today as Bezner steps into his new role as the 2023 Chairman of Texas Cattle Feeders Association.

United Front

Bezner’s history with TCFA goes back to the 1970s as his family were early members of the organization. After witnessing firsthand what TCFA does for its feedyard members, he decided to get involved and participated in its leadership program in 2002. “The services we are able to utilize with TCFA staff make life much easier for the smaller, independent feedyards,” he says. “From their Beef Quality Assurance (BQA) program to the environmental visits and insurance, it keeps us from having to hire more employees to do these jobs.” From there, he sat on several TCFA committees and served his first term on the TCFA board of directors from 2006 through 2008. After again being named to the board, he was elected as the 2021 vice chairman, then chairman-elect in 2022. He took the reins of chairman in 2023. Like all things in life, the more involved he became with the organization, the more he learned. That is especially true when it comes to TCFA’s political presence in both Austin and Washington D.C. With the Biden administration’s new definition of Waters of the United States (WOTUS) and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) action to list the lesser prairie chicken as endangered, TCFA, along with Bezner, hit the ground running this year to represent cattle feeders at both the state and federal level. In the months ahead, he is also ready to confront other key topics like fake meat labeling and traceability. Bezner notes it is important to keep a united front on these issues not just with TCFA members but with producers in other state associations, too. “I think with TCFA’s leadership, we can find common ground on these issues we all are facing,” he says. “We have to join forces and make sure that we keep a business environment in our industry so that we can be successful and continue to work without adding more costs and regulations.” Part of that continued success also relies on consumer trust—something Bezner is determined to earn. When asked what he wants the world to know about cattle feeding, Bezner stressed producers’ daily dedication to responsibly raising high quality and nutritious beef. “It’s so important for consumers to have faith in our product,” he says. “Whether it’s managing our natural resources, ensuring cattle health and wellbeing or taking care of our employees, everything we do affects our bottom line. So, we have every incentive in the world to produce beef in the safest and most efficient way possible.” Those incentives of efficiency prove true as Bezner points out U.S. farmers and ranchers produce 18 percent of the world’s beef with only 6 percent of the world’s cattle population. Bezner credits this with industry advancements in technology, nutrition, cattle genetics and an overall desire to maintain livelihoods for generations to come. From producing beef responsibly to representing cattle feeders’ interests at the capitol, TCFA President and CEO Ben Weinheimer says consumers and TCFA members alike can trust in Bezner to get the job done. “Michael Bezner encompasses everything a strong leader should be,” Weinheimer says. “His hard work ethic and genuine love for the industry is contagious, and we are lucky to have him represent our membership.” During his leadership, Bezner invites the input of all TCFA members. “I am honored to serve as chairman,” Bezner says. “I look forward to accomplishing the goals of TCFA set by our members. I ask that anyone with concerns or ideas know that my door is always open. We are in this together, and I want to know what you are thinking.” With his lifetime of production experience, this industry isn’t just a passion of Bezner’s. It’s his home. And he is ready to do everything in his power to protect it. By Madeleine Bezner TCFA Excellence in Environmental Stewardship and Beef Quality Assurance Award Recipients

Dimmitt Feedyard, owned by Dean Cluck Feedyard Inc. and managed by Ben Fort, received the 2022 Excellence in Beef Quality Assurance (BQA) Award for its outstanding commitment to beef quality assurance. Dimmitt Feedyard is located west of Dimmitt, Texas, in the Texas panhandle. The operation is a 50,000 head capacity feedyard that feeds both company and customer cattle.

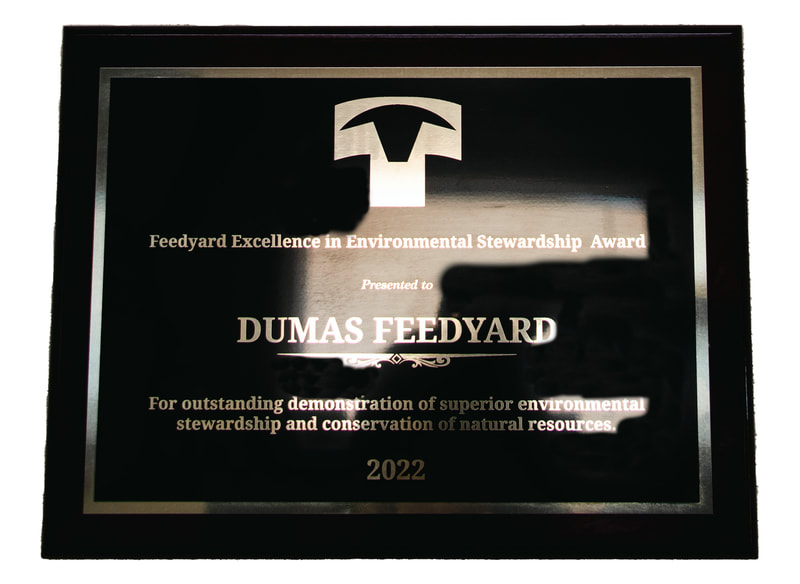

BQA begins day one of every new hire at Dimmitt Feedyard as training is integrated into the orientation process with a video presentation conducted in both English and Spanish. “The purpose and content are to communicate a comprehensive approach that is an expectation of each and every employee at Dimmitt Feedyard,” Ben Fort said. “Everyone takes this responsibility personally, and we take the outcomes personal as well.” Fort explains that the people at Dimmitt Feedyard and their daily commitment to enhance consumer confidence in the beef industry is what promotes the company’s success when it comes to best BQA practices and success. “Dimmitt Feedyard management and owners believe an excellent BQA program is intense on the front of all personnel and productions system,” Fort said. “It’s also a continual improvement effort for us.” Transparency is a key component when any new technology or best management practices are implemented. Dimmitt Feedyard strives for “zero corrective actions needed” after any in-house audit. Everything from feed manufacturing and delivery to pen maintenance and manure removal is documented by employees using technology. Additionally, accurate and accessible health records are maintained daily and are the responsibility of trained accounting clerks and trained cattle processing and doctoring crews. As part of Dimmitt Feedyard’s quest to cultivate a strong work environment, supervisors meet weekly on Mondays throughout the year to communicate each department’s production and BQA plans for the upcoming week, along with reporting opportunities for improvement to existing management practices. Visit Dimmitt Feedyard on any given day and you’ll find the employees are the foundation of its BQA program. “Our success is based upon their hard work and dedication,” Fort said. “The employees are committed and take these standards personal and strive to live above and beyond the standard.” Beyond the employees at Dimmitt Feedyard, the management team hosts TCFA Feedyard Technician students and students from WTAMU’s Feedyard Management class throughout the year. “These audiences allow for BQA practices to be communicated as the standard or foundation for all production decisions,” Fort said. “Dimmitt Feedyard has taken the approach to focus on communicating these BQA principles to the next generation.” Cattle feeding is a multi-generational, resilient industry focused on responsible stewardship of both the land and the cattle that occupy it. TCFA congratulates Dumas Feedyard and Dimmitt Feedyard on their continued dedication to producing sustainable, wholesome beef for consumers worldwide.

Scott Anderson, the 2021 TCFA Chairman, has always been up for a challenge. In 1989, when Anderson was invited to take part in management of CRI Feeders in Guymon, Okla., the company was running, but needed a lot of work.

“We were trying to rebuild the place and do all kinds of things,” he said. “We would spend some 15-, 16-hour days, be totally worn out, but ready to come back the next day and work through the challenges.” The challenges were difficult but rewarding. Today, CRI Feeders is a successful performance-oriented, customer-cattle focused feedyard. The goal is to provide an unmatched level of care and service for their customer’s livestock and do so by respecting customers and employees with integrity. Anderson’s love for the industry is attributed, not only to the challenges it poses, but also to the people who work alongside him, both inside and outside the feedyard. “The people are one of the best things about this industry,” he said. “There’s a cooperativeness that parallels the competitiveness between different feedyards. That is fun and challenging.” Anderson grew up in Blair, Neb. His family owned a diversified livestock and grain farm. He showed his first bred heifer in 1973 through his county 4-H program and continued to show both cattle and pigs every year until graduation. “The sows graduated from the farm at the same time I did,” he laughed. Anderson later attended the University of Nebraska where he earned a bachelor’s degree in animal science and a master’s in ruminant nutrition. In the summer of 1986, he left Nebraska and moved to Kansas to work at the K-State research feedlot. After a year as a sales nutritionist, he was offered the job of assistant manager at CRI. Ten years later, Anderson left the yard to work for a technology company that focused on feedyard cattle, but it wasn’t long before another Guymon area feedyard approached him to take over the manager job. In 2004, CRI wanted Anderson back, and he has been there ever since. The industry has evolved since then and will certainly evolve again, a challenge that is not lost on Anderson. “At one time we thought we were a mature industry, but it just continues to evolve,” he said. “For instance, we looked back at old showlists from the late 80s and early 90s. Back then we’d trade cattle two or three times during the week, and there would be a $2 to $4-$5 range in what those cattle brought. Each week all the packers came out and it was competitive. However, the emphasis then was to get them good enough to sell and roll them as we quick as we could.” By the end of the 90s, that had shifted, he noted, but there were reasons for that. Early on the industry focused on domestic demand and a shift to higher-quality, griddable cattle followed. “Today, it is a global market and we must look at so many factors, like how the U.S. dollar is trading and what is happening around the world,” he said. “It’s a completely different ballgame.” According to Anderson, continuing to perfect how to market cattle is one of the industry’s biggest challenges, but he is confident there will be solutions, and that optimism is necessary considering the many challenges the industry must tackle. NCBA’s negotiated trade working group, on which TCFA’s Chairman-Elect Kevin Buse serves, is developing a plan to address the appropriate level of negotiated trade to achieve price discovery. “We must and will find an industry-led solution so Congress and USDA don’t eliminate a feeder’s choice on marketing cattle,” he said. “Today, the beef industry is facing several issues that impact our future, and quite frankly, the sustainability of our collective business,” he said. “As producers, we are proud of our independent nature. That liberty has allowed us to explore and innovate new ways of adapting our production practices to fit the wide range of resources available in our specific geographical regions,” he said. “And because of this, the U.S. beef production system is the envy of the world in terms of efficient production and consistent, high-quality, wholesome beef. This freedom has created a wide array of successful business models across the regions.”

But, as Anderson noted, the industry still produces and markets the majority of product as a commodity, and those channels are very subject to the influences of supply and demand and the inherent volatility of the free market.

“We have weathered market-moving events many times in our history,” he said. “Those events are usually short lived, and the market adjusts. But during the last 12 months, we have experienced two major mark-moving events within a compact time frame that have compounded losses.” While the Holcomb fire in August 2019 had a somewhat predictable path to resolution, COVID-19 is unlike anything the industry has seen before. “Consequently, volatility continues to complicate the market’s ability to correct itself,” he said. Adding to those challenges is marketing to a consumer that is not familiar in any way with how beef is produced. Those consumers ask good questions about production practices based on what they read or hear. Sometimes that raises doubts in their mind about beef production. “Supporting and growing our domestic demand hinges on how well we communicate with our customers and answer their questions,” he said. “We also must answer questions for our global customers.” Exports add an additional $350 of value per head. Maintaining current export markets and related carcass value is a priority, and also presents opportunity for growth. “Our sustainability as an industry relies on our ability to maintain, and grow, both domestic and export demand,” he said. Another key element to keep the industry successful well into the future is access to motivated, qualified employees. “Attracting talented people into our industry has never been more important,” Anderson said. “This is the biggest challenge we have outside of marketing our product. We must cultivate the talent and help people understand that there is a very viable career path in the fed beef industry. “Working in a feedyard should be considered destination employment rather than default employment,” he said. This is a challenge for which TCFA is actively seeking better solutions, one of the many services that make the Association so incredibly valuable. “The services the Association provides to support the industry are phenomenal,” Anderson said. “There are so many, and especially for independent yards, like ours, to have employee safety, BQA, HR and environmental resources at your fingertips is such an asset.” Ross Wilson, president and CEO of TCFA, said Anderson is focused, deliberate and thoughtful in his efforts to do what is best for the industry. “He continues to look for ways to better the industry,” Wilson said. “He’s determined, a required skill for any feedyard owner in this climate, but particularly important for those brave enough to lead.” It is important to note that, while Texas Cattle Feeders Association bears the name Texas, the membership is comprised of feeders and feedyards in the three-state region of Texas, Oklahoma and New Mexico. “Leaders from all three states play a huge role in improving the industry,” Wilson said. Anderson’s influence and respect does not end in the three-state region. He has served the industry on a national level through his role as Secretary/Treasurer of the U.S. Roundtable for Sustainable Beef and on the Board of Directors of the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association. “Scott is dedicated to the industry he loves,” Wilson said. “He’s volunteered his time to better the entire industry, and that is not a simple task when you’re also running a feedyard.” No doubt Anderson has tenacity. Beginning in 2012, he made the decision to pursue a three-year quest toward a Ph.D. in business administration and organizational behavior, but he didn’t step back from his role at the feedyard. “Scott did both,” Wilson said. “That says quite a bit about his determination and work ethic.” It is a good thing Anderson prefers a challenge and that he is determined to meet it. What 2020 taught us is that no challenge is off-limits, and it will take a steady hand to lead the cattle feeding industry through these uncharted waters.

By: Carmen Fenton, Director of Communications

No two days are ever the same for Armondo De La Cruz. He has learned to expect the unexpected. “If a truck breaks down, everything stops,” he says. The feedyard depends on De La Cruz to keep machinery and vehicles operating. He has worked at the feedyard for 35 years doing a number of jobs from throwing hay, batching and loading, to calling feed. But he thrives in work that requires meticulous and steady hands. “We run the shop department,” he says. “We do the maintenance on the trucks, brakes, water pumps, anything that we need to do. The feed trucks, the corn haulers and the vehicles here in the yard.” His dad, a mechanic by trade, moved his family from Laredo to Hereford when De La Cruz was a young boy. It was his dad who gave De La Cruz his first lesson in mechanics. That is something he has passed on to both of his sons. “My dad was a mechanic, and that’s where I learned,” Cruz says. “And I got my younger son here now, and he’s learning. And my older son, he also worked here with me.” Hereford is home for De La Cruz and his family. He and his wife raised three children (two sons and a daughter) in the area. Now, they have grandkids, which De La Cruz says is “awesome” since you can sugar them up and send them back to their parents. When asked what advice he would give to a young man or woman wanting to get into the mechanical field, he smiles and says, “Just love what you do, and the rest will take care of itself.” It is clear that advice helped Cruz along the way. “I mean it sounds corny,” he says. “But if you like it, that’s good. And then if you can crack a smile on your face every day, it’s probably better stuff.”

Suzy Hicks and Cindy Shipp can be best described as a dynamic duo. The pair has worked together for almost 20 years at Dawn Custom Cattle Feeders.

Hicks, office manager, began working at the feedyard when it opened its doors. She’s often the first person to greet customers when they walk through the front door. She also keeps track of every transaction made at the feedyard. “Whatever they do today, I'll put in my computer tomorrow,” Hicks says. “Medicine, feed, anything pertaining to the cattle, I keep track of it.” In an office three feet from Hick’s front desk, Shipp, controller, manages the feedyard’s financials. Everything from payroll to receivables. “No day is the same in a feedyard,” Shipp says. “It's all different. It’s a new world every day.” Suzy and Cindy attribute their loyalty to the people they work with. “We've got a great crew who gets along really well,” Hicks says, “which makes it easy to come to work every day.” Shipp says there is an understanding amongst the employees that everyone gets to work and does their job. “We all know our jobs here,” Shipp says. “You work hard, get it done, and people show you respect.” When asked what they like most about their jobs, both are quick to acknowledge one another and their ability to work well together. “You know, I can tell when Cindy's got a lot on her plate,” Hicks says. “We both know when to let each other work, but we also know when to chat and have a cup of coffee.” Both women exhibit gracious cooperation and hard work, two characteristics necessary for success at a feedyard.

For cattle on a feedyard, perhaps few things are as important as a steady mill operation.

It’s 5:30 a.m. when Manuel Joven arrives at the feedyard and makes his way to the feed mill. His crew is running rolls, prepping boilers and flaking corn for the day’s feed. For the more than 50,000 head of cattle that call the feedyard home, perhaps few things are as important as a steady mill operation.

A calm, laid-back morning is a sign the day is off to a good start, and as Joven puts it, “The mill should be very consistent. You want to predict what time you will make your first round of feed, second round, third round and special rations. You want to predict what time you will be done at the end of the day.” For Joven, managing the feed mill is the culmination of years of learning. Born in Mexico, he moved to Texas when he was nine years old and worked summers in the feedyard while in high school. His dad, brother, uncle and cousin all work alongside him, and Joven credits each of them for teaching him the ropes. “My dad operates the loader, so that’s how I got my background with the loader,” he says. “I’ve got an uncle that works in the mill with me, so I picked up a bunch on gear boxes, motors, belts, drags, chains — everything that goes on in the mill, I learned from him.” Similarly, his brother drives a feed truck and his cousin is the head doctor. “They know how to do the work,” Joven says. “I learned that from them. Now I know how to do the work as well.” Every morning, Joven climbs to the top of the mill and observes the yard. From there he can see if everything is running smoothly, take note of where the feed trucks are and where cattle are moving. It’s up top where Joven listens to the mill. “A bearing could start making a different noise. An auger may be rubbing against a trough,” he says. “You may just go up there, enjoy the breeze and come back down and all is good. But you stop doing that, there’s going to be one day that you could’ve prevented something.” Joven loves what he does and the industry he works in. He says the more time you spend paying attention to details, the quicker you respond to challenges before they become problems. “Little things you start looking at, like inspection doors, the bearings, the motors, the gear boxes,” he says. “Just touch them. If they’re getting hot, it is probably because they’re not lubed correctly.” Joven has had a steady mill crew for five years, a milestone he is proud of considering that long hours and manual labor can lead to high turnover. Keeping his crew around for the long haul keeps for calmer, more consistent days. “It’s tough. It’s not easy. You just got to have a passion for it,” Joven says. “But keep the guys safe, keep the guys motivated and it turns out to be pretty good.”

Carmen Fenton is the communications director for the Texas Cattle Feeders Association. She's also mom to Ella Jane (9), Hays (8) and Lane (2).

For Randy Shields, understanding his employees is the key to ensuring the utmost care for 50,000 head of cattle at Wrangler Feedyard. A general manager for almost 10 years, Shields emphasizes teamwork to create and execute feedyard operations each day.

“We all work together. We've got to get the cattle fed. They've all got to be watered. The pens need to be rode. It takes teamwork to make that happen,” Shields says. “Understanding people's strengths and weaknesses, even understanding your own is probably the biggest key to me. You have to make sure you're able to see that, place the right people in the right places, and then let them do their job.” Shields’ passion for people and the industry stems from his upbringing at the family ranch, his college education and 21 years of experience. He began working for Cactus Feeders after graduating from West Texas A&M University. Since then he has worked as cattle foreman, feed foreman, mill manager and assistant manager. In his current role he oversees all aspects of the feedyard from the cattle and feed departments to the yard crew and office management, an ideal role for Shields given his diverse past work experience.

“You've got the mill producing the feed. You've got the feed delivery department delivering the feed. You've got the cattle department going out and doing the daily duties of riding pens, taking care of the cattle,” he says. “Of course, at the end of the day, all these things come together. We do what we do to take care of the cattle.”

Although Shields’ job revolves around managing employees and overseeing day-to-day operations, his passion for the industry extends outside the feedyard. Wrangler Feedyard hosts over 100 tours a year. Teaching groups from across the world about U.S. beef production is something Shields says is crucial. “I think a challenge we have today is that only two percent of the population is involved in agriculture. Making sure folks are informed of what we do, why we do it, and how we do it is a very important thing,” he says. “That’s the reason we do tours. We have a story to tell. If we don't tell it, somebody else will tell it for us.” Spend a morning with Shields and you’ll quickly learn the amount of enthusiasm and commitment he puts toward managing the people and cattle under his care. He’s the quintessential man in charge — diligent, positive and willing to work with others to achieve success. “I enjoy working with people. I love knowing that the product we're producing is the highest-quality protein source on the market,” he says. “Call it cliché, but we’re helping feed the world. All of us working toward the same goal to create a wholesome product that we can send to the public is pretty amazing.”

Madeleine Bezner is the communications coordinator for the Texas Cattle Feeders Association. She grew up in Dalhart, Texas where her family owns and operates a feedyard.

Samantha Bell did not grow up in agriculture. She grew up in town, only a short distance from the Texas Cattle Feeders Association office in Amarillo. That’s fitting, considering she’s held just about every job in the cattle feeding business.

She’s been an office manager, a feedyard manager and prides herself on being able to do every job on the yard — both in case she’s ever needed, and to make sure others know she understands the role they play and challenges they face. But it wasn’t easy getting there. She recalls a time she didn’t know what she was doing. “I remember early on, when I first realized I wanted this to be a career and not just a paycheck, I was weighing trucks, commodity clerking and doing feed cards,” Bell says. “The cattle clerk came out and showed me a closeout, and it was probably the first time I'd ever seen one done. I pretended I knew exactly what was happening, but I really had no idea what any of it meant.” Bell asked if she could make a copy of the closeout, took it back to her desk and proceeded to break it down line by line. That’s when she realized how much she loved the numbers side of the business.

Today, Samantha serves as the Controller of Double D Feedyard in Dimmitt where she oversees every aspect of the company’s finances including payroll and accounting.

A woman’s work at a feedyard isn’t limited to just office jobs, Bell says. The fact that more women are serving in various roles within the industry makes her proud. “When I first started, there were hardly any women outside of office manager or administrative-type jobs,” she says. “Those roles are important, but today there are women riding pens, managing feedyards, doing just about every job on the payroll.”

She says the cattle feeding industry is a great place to work, and she would absolutely recommend it to other women, with the following advice:

“Know what you know and own it. Do not be afraid to voice it, but also don’t be afraid to admit a mistake,” she says. “Just be real, and work hard. The industry may not be the right fit for every woman, but it’s a great fit for some.” “If my daughter came up to me today and said, ‘Mom, show me the ropes,’ I would say, ‘Let's go!’” she adds. “Because it is kind of fun as a woman to say, ‘I can do that.’” |

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

About TCFA |

Get Involved |

|