|

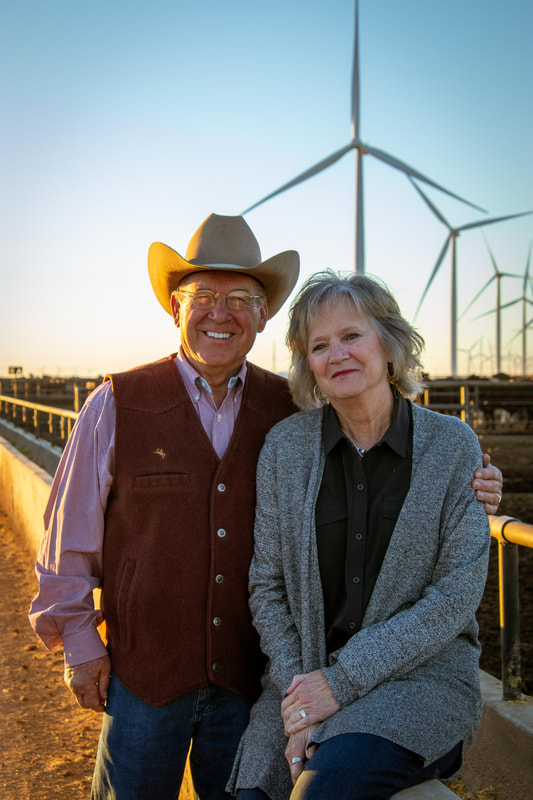

Kirkland Feedyard

Perry, Robby and Carson Kirkland

Perry Kirkland said he knew nothing about feeding cattle when he began Kirkland Feedyard in 1983. In fact, he fell into the business by accident. He and his wife Melanie purchased land to expand their farm. The cattle pens came as a bonus.

It took some encouraging from his neighbors, but eventually, armed with determination, a pickup and buckets of corn, the couple made their start in the business. Perry said he quickly learned the harder you work, the more successful you could be. In those early days of the feedyard, securing financing was the biggest challenge. It was hard to get bankers to understand the bigger vision, Perry said. “It was really a struggle to grow from scratch.” But despite challenges, the yard grew from an 800-head, primarily preconditioning yard to a larger operation. “We finally bought a feed truck and continued to build and grow slowly as a one-man operation until 1995, when Robby came back and joined us.” Robby Kirkland was just out of college in 1995, and it wasn’t always his plan to come back to the family feedyard. “My dad was really good about saying, you know, there’s opportunity here,” he said, “but don’t feel obligated. You’ve got to know what you want to do.”

When Robby and his then-fiancé Amy made the decision to go all in, Robby learned how to do everything from riding pens, running the mill and shipping cattle.

“That probably taught me as much about feeding and feeding cattle as anything,” he said. “It allowed me to learn.” Together, Perry and Melanie, Robby and Amy have grown a successful custom feedyard with a strong and loyal customer base. Their customers rely on them to market and protect their cattle investment, and that’s a job they take pride in. It’s a reputation they hope to pass on to Robby’s son Carson. Carson, a freshman animal science major at Texas Tech University, plans to come back and work at the feedyard and continue the legacy of hard work and determination the family is known for. He said once he was old enough to realize what his grandpa and dad built, he knew he wanted to be a part of it. “I’ve seen my grandpa a month after his heart surgery, back working already,” Carson said. “And I’ve seen my dad coming in late at night and going to work early in the morning, and my Mimi and my mom, working right alongside them.” No doubt the feedyard life presents challenges. Finding and retaining a skilled workforce and marketing cattle are two of the most pressing issues facing the industry. These issues will likely be top-of-mind for cattle feeders long after Carson takes the reins. “The marketing aspect of the cattle is a real issue,” Perry said. “It was an issue when I was sitting behind the manager’s desk, and it’s an issue that will continue to need to be addressed in the future.” While Carson plans to keep the family business going, his sisters, Calleigh and Cydney, said the lessons they learned watching their parents and grandparents gave them the confidence to be successful themselves. Calleigh, now in her senior year at Texas Tech, is working toward a master’s degree in speech pathology. She plans to open her own practice. My family showed me that if I want to do something, I can go do it. Just like they did, she said. “I’ve watched my grandparents and parents work hard to become successful. They started from basically the bottom, and they worked hard.” Cydney, the youngest Kirkland, said that her family has shown her what hard work really means. “They are strong through it all. They’ve taught me to do lots of good things.” “It’s awesome to see the family business handed down, but more than that,” Robby said, “it’s awesome that the next generation wants to continue.” As anyone in the feedyard business will tell you, it takes more than hard work to be successful. “I’ve told them all that farming and agriculture is not a job. It’s a passion, and you have to have that passion to be a success,” Perry said.

Scott Anderson, TCFA Chairman

As Earth Day approaches, those of us involved in production agriculture would like to share our appreciation for taking care of the environment. Since our livelihood and future relies upon making sure we leave this earth better than we found it, we believe it is critical to share how serious we take our responsibility as stewards of the land and animals we care for.

There is a common misconception that U.S. agriculture, especially animal agriculture, is a major greenhouse gas contributor. However, from a holistic perspective, the U.S. agriculture and timber system is a net carbon sink. This means that, collectively, the system removes more carbon than it emits. In many countries’ forestland is viewed as reserve farmland to be cleared and used for food production when additional food resources are needed to feed a nation’s growing population. Because of the productivity of U.S. farmers and beef producers who utilize 800 million acres of range and pastureland, we as a country can preserve our forestland. Over the last 100 years we have added about 40 million acres of forestland in the United States. This was accomplished while also building 200 million more homes, feeding a population that is three times larger than it was in 1920, and exporting 15 to 20% of production. Yet, we are still a net carbon sink. A primary contributor to this productivity is the unique digestive system of a beef animal. Cattle consume grasses, forages and other food by-products and “up-cycle” them into a delicious, nutrient dense wholesome protein source for humans. In total, about 90% of what a beef animal eats is inedible by humans. Even a grain-finished beef animal in the U.S. generates 19% more protein for the human supply than it consumes. There is also talk about “cow burps” and their contribution to global warming. As the beef animal digests grasses and forages they eat, they expel methane. However, this biogenic methane is part of a carbon cycle that has been happening as long as ruminants have walked the earth. This cycle does not create any “new” carbon. The same carbon cycles from plant to animal to air and then through photosynthesis in the plant, CO2 is pulled out of the air back into the plant to be consumed by another beef animal next year. This cycle has been repeating for centuries. Beef producers in the United States are continuously looking for ways to manage their resources better and to improve the efficiency of their production practices. We produce 18% of the world’s beef with only 6% of the world’s cattle. That is producing more beef with less resources. The U.S. production model is the envy of the world. And we still work hard to make it better every day. As we celebrate Earth Day, please remember that every day is Earth Day for beef producers. Beef production is sustainable and part of the climate solution. |

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

About TCFA |

Get Involved |

|